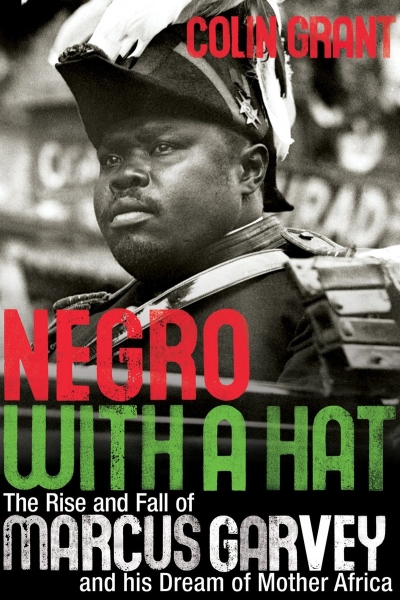

Negro With A Hat: The Rise And Fall Of Marcus Garvey by Colin Grant

Negro With A Hat: The Rise And Fall Of Marcus Garvey by Colin Grant is richly evocative of the times and places in which he lived and the people who mentored, admired, and quarreled with him.

In the back catalogue of Garvey’s meteoric rise to fame, in photo after photo, Garvey poses as the very model of the civilised, self-improved man. He is hardly ever seen without his hat: there is Garvey with academic mortar-board; Garvey in pith helmet and plumes; Garvey with a fedora.

Marcus Garvey recognised that a large part of the problem of black people lay in the perception of white people. He chose to address this conundrum by using the language of the dominant groups, and that language was both vocal and visual.

In the image of Marcus Garvey, of a proud ‘Negro with a Hat’, resides the lust for distinction. In his plumed helmet and military uniform, Marcus Garvey put on the toga of race pride.

Finally, in the roll call of black heroes in the hall of fame, Marcus Garvey occupies a unique position; he’s often depicted hovering somewhere between a craved-for messiah and pathological clown. Negro with a Hat suggests that ambivalence as it evokes the past, causing discomfort and underscoring the enigma of Marcus Garvey: visionary or buffoon? Garvey, I found, was a polarizing figure. And in the polemic that surrounds him, something of the human being was lost, was crusted over. Characterisations of him were monochromatic, and in writing about Garvey, I sought to draw on a richer palette. His short-comings and the tragic-comic events surrounding some aspects of his life would not be glossed over.

But all through the telling, I would pay attention to the words of John B. Russwurm, a Jamaican predecessor of Garvey and publisher of an early black journal. In answer to the patronising tendencies of even the most well-meaning commentators, Russwurm wrote that he was determined to give readers a more accurate portrayal of black life because ‘too long have others spoke for us [such that] our vices and our degradations are ever arrayed against us, but our virtues are passed unnoticed.’

Introduction

‘Marcus Garvey: Lunatic or traitor.’ That was the assessment of W.E.B. Du Bois, the Jamaican’s nemesis and rival for the leadership of 1920s black America. In a withering editorial, Du Bois called for Garvey to be locked up or deported from the U.S.A – a wish that came to pass, on both counts.

Thereafter, especially following his death in 1940, the story of Marcus Garvey was largely told from the perspective of his enemies. He was depicted as gauche and bombastic with an embarrassing penchant for dressing up in out-dated Victorian military costumes, complete with epaulettes, ceremonial sword and plumed bicornate helmet. The title [Negro with a Hat], which had proved elusive, suddenly arrived unbidden in 2003, when I stumbled across an exhibition that inadvertently offered a new way at looking at Marcus Garvey.

‘Make Life Beautiful’, the exhibition of ‘The Dandy in Photography’ that toured the UK that year was conforming to type with its alluring, black and white images, when half-way round the gallery, I was pulled up sharply by one print – the profile of an anonymous black man wearing a fedora. The caption read: ‘Negro with Hat’. Adjacent to it was another portrait by the same photographer; it showed a white man in fancy dress wearing a theatrical turban. It’s title: ‘Man with Hat.’ The juxtaposition seemed to pose a question: is a Negro not a man?

When, just over a century ago, the aristocratic photographer, F. Holland Day placed his camera in the service of the anonymous black model, the elegant studio-based portrait of the ‘Negro’ that he produced was intended to be formal and respectful. This was a subject who dignified the term ‘Negro’ – a forerunner of Sidney Poitier whose clean finger nails and starched white shirt graced the silver screen.Today ‘Negro’ is a charged word that provokes unease and is a reminder of past humiliations.

The exhibition ‘Make Life Beautiful,’ was no exercise in revisionism; there was no nod towards modern sensibility, and I was disturbed by the caption ‘Negro with Hat’ which was included without explanation. But later, when I began to compose my biography of Marcus Garvey, I reached for that title. No publisher would print a book called Negro with a Hat unless it was clearly ironical. There was, of course, a danger that the title would be misunderstood or be considered ‘unfortunate’, as it still held the possibility of both respect and abuse. But, ultimately, it captured the conundrum of Marcus Garvey: a proud Negro who was revered and reviled in equal measure. Marcus Garvey, the great ‘ebony sage’ of 1920s, embraced the word ‘Negro’; to him it was a badge of honour.

In August 1920, Garvey master-minded the first international convention of the ‘Negro People of the World’. With a mixture of old-world pageantry and new-world carnival, 25,000 of his supporters marched from the headquarters in Harlem to Madison Square Garden. They had gathered to participate in a ‘racial sacrament’ to witness the elevation of the small stocky Jamaican immigrant, dressed in imperial military regalia, as the ‘provisional president of Africa.’

At the end of that convention, Garvey published a declaration of rights for the Negro People of the World. Declaration No 12 proclaimed that henceforth the black man would no longer answer to ‘nigger’ but only to ‘Negro.’ In 1930 the New York Times followed Garvey’s lead, producing a style guidebook in which ‘Negro’ would be forever capitalised. Marcus Garvey was a man of grand, purposeful gestures. His deportment was key. Where critics saw embarrassing pretension, admirers revelled in his dignified Edwardian demeanour. With his shrewd promoter’s eye, Garvey understood the power of presentation. He even went so far as to employ James Van Der Zee, the unofficial photographer of the Harlem Renaissance, to capture the [UNIA’s] spectacular parades.

About the Author

Grant’s attention to the exceptional women in Garvey’s life, particularly his wives Amy Ashwood and later Amy Jacques is especially noteworthy. Garvey, the radical journalist and editor (The Negro World), emerges more fully than usual, with all his contradictions present. Dense with detail, but consistently readable, this splendid book is certain to become the definitive biography. Garvey was a dreamer and a doer; Grant captures the fascination of both.

Colin Grant is the author of the critically acclaimed biography Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey and His Dream of Mother Africa, (Jonathan Cape, 2008; Oxford University Press, USA , 2008). Grant is an independent historian and BBC radio producer. He joined the BBC in 1991, and has worked as a TV script editor and radio producer of arts and science programmes on radio 4 and the World Service. He has written and directed plays including The Clinic, based on the lives of the photojournalists, Tim Page and Don McCullin.

Grant has written and produced several radio drama-documentaries including: African Man of Letters: The Life of Ignatius Sancho A Fountain of Tears: The Murder of Federico Garcia Lorca Move over Charlie Brown: The Rise of Boondocks

Purchase the book from Amazon Waterstones

Visit Colin Grant website for more information.